Active Galactic Nuclei Observing Program

Active Galactic Nuclei Observing Program Coordinator:Al Lamperti |

|

Introduction

|

|

Background

Galaxies with active nuclei were studied in the early 1940s by Minkowski, Humason and Seyfert. Some ‘variable’ stars were later found to be categorized as Active Galactic Nuclei (AGN), including BL Lacertae objects. Radio galaxies were studied in the 1950s followed in the 1960s by quasi-stellar objects (QSO; quasars). Beginning in the 1980’s the numbers of known QSO, BLO and AGN objects have grown almost exponentially1, particularly due to those discovered by the Sloan Digital Sky Survey.

Active Galactic Nuclei are the highly energetic compact regions at the centers of some galaxies and are the most luminous sources of electromagnetic radiation in the universe. They are powered by a supermassive black hole and some have strong emission lines.

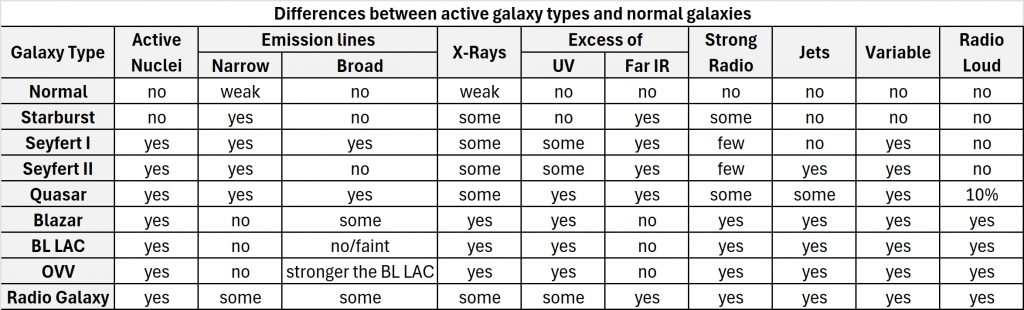

The following Table describes the differences of the various types of active galaxies as compared to normal galaxies:

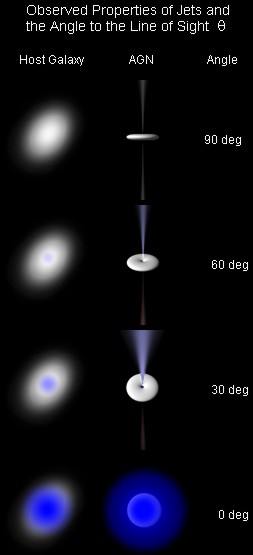

Currently, many investigators are using “orientation-based” unified models to explain some of the differences between active galaxy types. The types seen depend upon the angle from which we are observing the object, as depicted in Figure 1.

Seyfert II

Seyfert I, Quasar

Quasar

Blazar

Figure 1. An orientation-based unified model of AGN

Types of Active Galactic Nuclei:

Although radio galaxies are also included under the AGN umbrella, they are not part of this particular A. L. Program (though they are a part of the Radio Astronomy Observing Program of the Astronomical League). Here we are concentrating on those AGNs that emit much of their energy in the visible wavelengths.

- Blazars (Blazing quasi-stellar objects) – These have relativistic jets pointing toward Earth and are of two types:

- BL Lacertae Object (BLO) – This is a variable AGN hosted in a massive galaxy.

- Optically Violent Variables (OVV) – These are highly variable AGNs, which are very few in number. These radio galaxies have light output that can change dramatically over a very short period of time. They differ from BLOs by having broader emission lines and higher red shifts.

- Quasars – These are extremely bright AGNs, so bright that their light often overpowers that of the rest of the hosting galaxy. This is an important property of quasars. Subgroups of quasars will be discussed in the next section.

- Seyferts – These are almost exclusively spiral galaxies. In contrast to quasars, Seyfert galaxies have AGNs that are less luminous making the rest of the galaxy visible to us.

- Seyfert Type I – These have narrow and broad bands of spectral lines of ionized hydrogen, helium, nitrogen and oxygen.

- Seyfert Type II – These only have a narrow band of spectral lines.

Both Seyfert Types I and II fluctuate rapidly, especially in the X-ray portion of the spectrum.2

Types in between I and II, e.g., Sy 1.2, Sy 1.5, denote differences in the appearance of the optical spectrum. Seyfert galaxies can also be categorized by Luminosity Classes I-V, with galaxies of a Luminosity Class I being the most massive, having the largest number of stars and having the most strength, greatest thickness and the most prominent arms.

All of these distant AGNs display redshifts (z values) that correspond to a few hundred million light years to several billions of light years. These would be their proper distance and not the expanding distance.

Gravitationally-Lensed Quasars:

This is one of two unusual subgroups of quasars. In this type, the light from the distant quasar is gravitationally-lensed by a massive foreground object, an effect predicted by Einstein’s General Theory of Relativity. In 1979 a twin quasar in Ursa Major was found. Each segment had identical spectra, leading to the conclusion that the light originated from a single source and was ‘split’ by a foreground object. This ‘optical illusion’ of multiple images of a single background object obviously requires the background object to be more distant than the closer, foreground ‘lensing’ object. Since most quasars are very distant, they are very susceptible to being gravitationally lensed. Lists of gravitationally lensed quasars can be found in an article by Wolfgang Steinicke3 and from the Gravitational Lens Database.4

True Double Quasars:

The first pair in this second subgroup of quasars was discovered by Djorgovsky several years after the discovery of the first lensed quasar. In this subgroup the spectrum of each quasar in the pair is different. That is the clue that we have two quasars here, not two images of a single quasar. Lists are available from references 3 & 4.

Lists of Galactic Nuclei:

Quasars, BL Lacertae Objects and Seyfert Galaxies:

Since the total number of known quasars and BLO objects is truly ‘astronomical,’ we have, for the most part, limited the list to those described by Wolfgang Steinicke in 19985, where he tabulated objects brighter than 16.5 magnitude and north of -20 degrees declination. For this Observing Program, we have chosen those Seyfert galaxies with a Luminosity Class of I and obtained the list from the NASA Extragalactic Database (NED)6 using that parameter. We also limited these Seyfert galaxies to those higher than -20 degrees declination.

Variable Galaxies:

Many AGNs are labeled variable as their energetic outputs have optical variations that can be captured, recorded and reported to the American Association of Variable Star Observers (AAVSO). For those wishing to participate in and contribute to Citizen Science, the list of variable galaxies in Appendix G may be used. In addition, a useful guide, “Observing Variable Galaxies” by Alvin Huey is available. It has finder charts and images of many of the variable galaxies on the list.

We encourage you to report any Variable Galaxies you observe to the AAVSO. You must register with the AAVSO to report your findings. You can also print their variable star plots for a given variable galaxy.

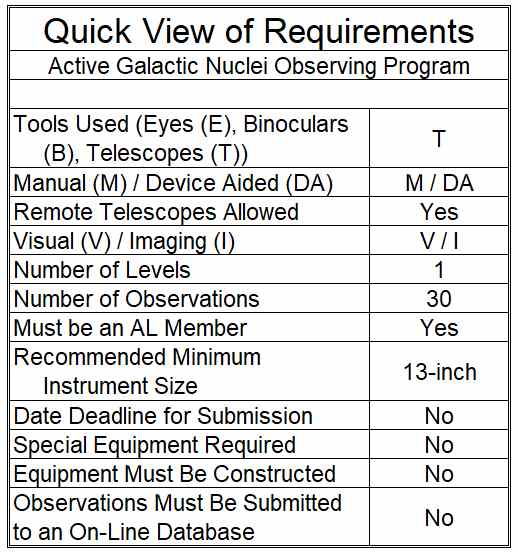

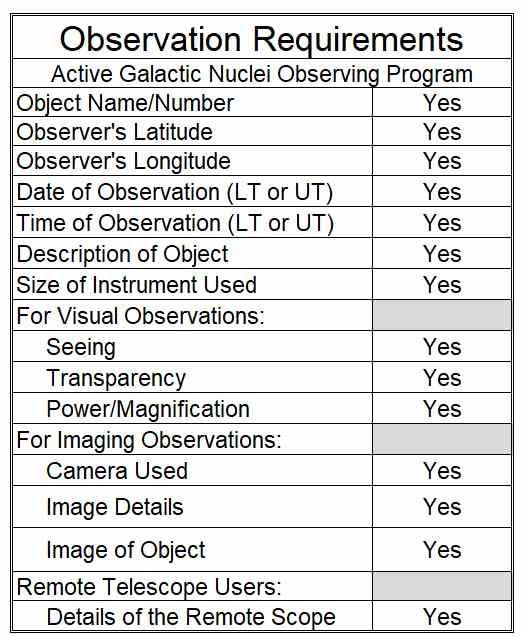

Requirements and Rules

This certification is available to members of the Astronomical League, either through their local astronomical society or as members at large. If you are not a member and would like to become one, check with your local astronomical society, search for a local society on the Astronomical League Website, or join as a member at large.

|

|

- Photographic or digital imaging observations, (at least a 4” telescope is suggested) the image must meet:

- All of the requirements for visual observers.

- The object must be indicated on the image with an arrow or line.

- Type of camera used.

- Total exposure time

- Size of field

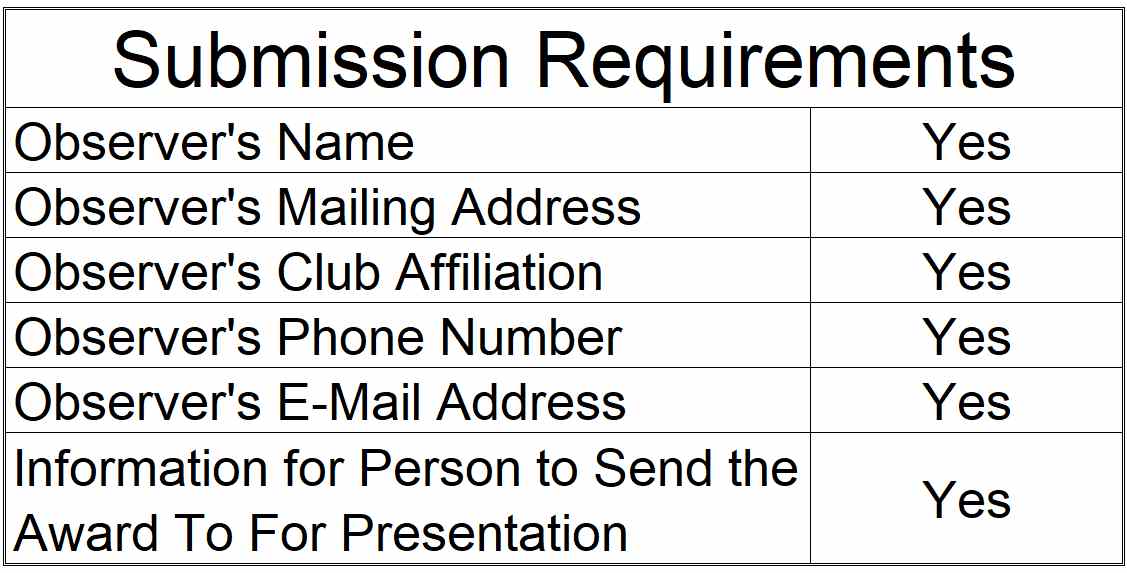

Submitting for Certification

| The log sheets and electronic files containing digital images (which can be submitted on a CD or through an internet-based delivery system – e.g., website, Drop Box, Google Drive, etc.) can either be sent to the Program Coordinator or to one of your astronomy club officers for verification.

The certificate will indicate the certificate number: a M for manual observations or an I for electronically imaged observations. |

|

Upon verification of your submission and of your active membership in the Astronomical League, your recognition (certificate, pin, etc.) will be sent to you or to the awards coordinator for your society, as you specified. Your name will also appear in an upcoming issue of the Reflector magazine and in the Astronomical League’s online database. Congratulations. Good luck with your next observing challenge.

Notes:

Acknowledgements:

John Bajtelsmit, Mark Huss, Vince Scheetz, Frank Colosimo and Joe Lamb of the Delaware Valley Amateur Astronomers contributed their expertise to the development of this Observing Program. Dick Steinberg provided the images used on the certificate. Aurore Simonnet of Sonoma University kindly gave permission to use her drawing of the quasar depicted on the pin.

Hints on Observing Quasars, BLOs, and AGNs:

The Wolfgang Steinicke reference5 is a very valuable tool in compiling a strategy for attacking these objects. To make things that much easier we also added the pages of the Uranometria (1st and 2nd editions) and Millennium star atlases. One may use other software programs such as MegaStar© for such purposes.

Preliminary ‘homework’ beforehand includes making an observing list for the upcoming session(s). The observing list will have the object name, constellation, magnitude, distance and page of Uranometria or page of Millennium. In the observing field, one would then star hop using the Uranometria atlas under low magnification and, if need be, star hop using the fainter stars plotted in the Millennium atlas. The image provided by the aforementioned website will prove helpful in determining which star-like object is the quasar. To view the dimmest objects, higher magnification is highly recommended. Once the object is located, then a verbal description can be dictated in a microcassette recorder and/or a rough sketch of the eyepiece field can be made. The appendices also provide the observer with the redshift (z)7. Having the distance of the object available to the observer at the eyepiece adds an additional sense of wonder, awe and satisfaction.

Time Delay Distances of Lensed Quasars:

Light from lensed quasars has been used to further confirm Einstein’s General Theory of Relativity. Calculations show that the light being lensed takes more time to travel around a massive foreground object to reach the observer, perhaps up to 0.3 years in one cited example.8

Citizen Science:

If you enjoyed this Observing Program, and look forward to doing more observations to submit to the national or international database, then we invite you to participate in the Astronomical League’s Citizen Science Program. This is an extension of this Observing Program. To participate you should be sure that any Variable Galaxy Observations you did as part of this Observing Program were submitted to AAVSO, and then continue to observe and submit those additional observations. For more information about this opportunity, please go to the website: Citizen Science Program.

Active Galactic Nuclei Observing Program Coordinator:Al Lamperti |

Links:

Appendices:

- Appendix A, Quasar list

- Appendix B, Seyfert list

- Appendix C, BLO list

- Appendix D, Gravitationally-lensed quasar list

- Appendix E, Double Quasar list

- Appendix F, Log Sheet

- Appendix G, Variable Galaxy List

References:

- 1 Veron-Cetty, M.-P. and Veron, P. A Catalogue of quasars and active galactic nuclei: 13th edition, Astronomy & Astrophysics 518: 1-8, 2010.

- 2 http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Active_galactic_nucleus

- 3 “Faint Objects and How to Observe Them”, Brian Cudnik, Chapter 5, “The Nature of Quasars and Other Exotics” Springer, 2013

- 4 “On False and True Double Quasars” Wolfgang Steinicke,

- http://www.klima-luft.de/steinicke/Artikel/dqso/dq_e.htm

- 5 http://www.cfa.harvard.edu/castles

- 6 “Catalogue of Bright Quasars and BL Lacertae Objects”, Wolfgang Steinicke http://www.klima-luft.de/steinicke/KHQ/khq_e.htm

- 7 http://ned.ipac.caltech.edu/forms/OBJatt.html

- 8www.ifa.hawaii.edu/users/kud/teaching_15/16_time_delay.pdf (p. 9), Rolf Kudritzki, 2015

Other References:

- “Active Galactic Nuclei and the Amateur” Hewitt, N. and Poyner, G. Deep Sky Observer 116: 3-13, 1999.

- “Observing Variable Galaxies” Alvin Huey, 2013 (http://faintfuzzies.com/DownloadableObservingGuides2.html)

- For the truly adventurous, “The million quasars (Milliquas) catalogue, version 3.4 (2013)” at http://quasars.org/milliquas.htm